Marranismo e Inscripción, o el abandono de la conciencia desdichada (Escolar & Mayo, 2016), el nuevo libro de Alberto Moreiras, es un compendio reflexivo sobre al estado teórico-político del campo latinoamericanista durante los últimos quince o veinte años. A lo largo de nueve capítulos, más una introducción y un epílogo, Moreiras traza en constelación una cartografía de numerosas posiciones de la teorización latinoamericana, sin dejar de inscribirse a sí mismo como actor dentro de una epocalidad que pudiéramos llamar ‘universitaria’, y cuyo último momento de reflujo fue el ‘subalternismo’. Además de bosquejar un mapa de posiciones académicas (postsubalternistas, neomarxistas, decoloniales, o deconstruccionistas), el libro también alienta una hermenéutica existencial que se hace cargo de lo que le acontece a la vida, y en su especificidad a la “vida académica”. Y los lectores podrán comprobar que lo que acontece no siempre es bueno. Marranismo e Inscripción explicita muy tempranamente en la introducción un tipo de denegación que configura el vórtice de este ejercicio autográfico: “…durante años pensé en mí mismo como alguien comprometido centralmente con el discurso universitario, como la institución universitaria. Hoy debo admitir que ya no – trato de hacer mi trabajo lo mejor posible, claro, pero algo ha cambiado. O seré yo el que cambió. Y entonces, para mí, ser un intelectual ha perdido ya su prestigio, el que una vez tuvo. Habrá quizás otras maneras de serlo en las que el goce que uno quiso buscar pueda todavía darse. Hoy ese goce, en la universidad, solo es ya posible contrauniversitariamente.” (Moreiras 16).

Marranismo e Inscripción, o el abandono de la conciencia desdichada (Escolar & Mayo, 2016), el nuevo libro de Alberto Moreiras, es un compendio reflexivo sobre al estado teórico-político del campo latinoamericanista durante los últimos quince o veinte años. A lo largo de nueve capítulos, más una introducción y un epílogo, Moreiras traza en constelación una cartografía de numerosas posiciones de la teorización latinoamericana, sin dejar de inscribirse a sí mismo como actor dentro de una epocalidad que pudiéramos llamar ‘universitaria’, y cuyo último momento de reflujo fue el ‘subalternismo’. Además de bosquejar un mapa de posiciones académicas (postsubalternistas, neomarxistas, decoloniales, o deconstruccionistas), el libro también alienta una hermenéutica existencial que se hace cargo de lo que le acontece a la vida, y en su especificidad a la “vida académica”. Y los lectores podrán comprobar que lo que acontece no siempre es bueno. Marranismo e Inscripción explicita muy tempranamente en la introducción un tipo de denegación que configura el vórtice de este ejercicio autográfico: “…durante años pensé en mí mismo como alguien comprometido centralmente con el discurso universitario, como la institución universitaria. Hoy debo admitir que ya no – trato de hacer mi trabajo lo mejor posible, claro, pero algo ha cambiado. O seré yo el que cambió. Y entonces, para mí, ser un intelectual ha perdido ya su prestigio, el que una vez tuvo. Habrá quizás otras maneras de serlo en las que el goce que uno quiso buscar pueda todavía darse. Hoy ese goce, en la universidad, solo es ya posible contrauniversitariamente.” (Moreiras 16).

La tesis a la que invita Marranismo es la de abandonar la crítica universitaria (y la conciencia desdichada es un producto de la creencia en el prestigio de la labor crítica) en al menos dos formulaciones principales. Por un lado, la función de la crítica como apéndice tutelar del saber universitario entregado a su tecnicidad reproductiva. Y en segundo término, tal vez menos vulgar aunque no menos importante, el abandono de la crítica como operación efectiva y suplente de la crisis interna de la universidad. El ejercicio autográfico marcaría una modalidad de éxodo de la suma total de la razón universitaria hacia lo que se asume como una estrategia hermenéutica que implica necesariamente la indagación de una situación concreta que da el paso imposible ‘del sujeto al predicado’ [1]. Pero el paso imposible del marrano solo dice su verdad no como persuasión interesada de un sujeto, sino como hermenéutica inscrita en cada situación irreducible al tiempo del saber. En el ejercicio hermenéutico, el marrano deshace íntegramente la incorporación metafórica, sin ofrecer a cambio una paideia ejemplar, un relato alternativo, o recursos para el relevo generacional. Es cierto, hay un llamado a cuidarse ante un peligro que acecha, aunque esto es distinto a decir que el libro está escrito desde una situación de peligro. En realidad, el tono del libro es de serenidad.

En un momento del libro, Moreiras escribe: “…el próximo expatriado potencial que lea esto debe saber a qué atenerse, y protegerse en lo que pueda” (Moreiras 18). La pregunta que surge en el corazón de Marranismo es si acaso la universidad contemporánea está en condiciones de ofrecer un mínimo principio de autoconservación de la vida del pensamiento; o si por el contrario, la universidad es solo posible como pliegue contrauniversitario post-crítico, léase poshegemónico, para seguir pensando en tiempos intempestivos, atravesados por el ascenso de nuevos fascismos, y entregado a la indiferenciación técnica del saber en el seno de la institución. O dicho con Moreiras: ¿habrá posibilidad de ‘mantenerse en pie’ en los próximos años? Y si hay posibilidad de hacerlo, ¿no es una forma de contribuir a mantener en reserva el general intellect en función de una ecuación humanista? (ej.: más saber + más estudiantes = más progreso; pudiera ejemplificar lo que queremos decir). Todo esto en momentos, dicho y aparte, en donde la lingüística aplicada o la pedagogía derrotan en rendimiento a la ya poco digna tarea del pensar. Y si es así, la universidad contemporánea no estaría en condiciones de ofrecer más que humanismo compensatorio, donde el pensador solo puede disfrazarse de civil servant de la acumulación espiritual de la Humanidad. Desde luego que no hay curas ni bálsamos para dar con una salida a lo que Moreiras se refiere como un futuro “incierto e indecible abierto a cualquier coyuntura, incluyendo la de su terminación” (Moreiras 57). Pero tal vez hayan formas más felices que otras de entrar en relación con el nihilismo universitario en sus varias manifestaciones opresivas.

Por eso es que me gustaría invitar a leer Marranismo e Inscripción como una contestación a las formas sofísticas dentro y fuera del campo académico, exacerbadas en el momento actual del agotamiento de la universidad en el interregno. Y como sabemos, el interregno no es más que la imposibilidad de hacer legible el pensamiento en el momento del fundamentalismo económico. Pero es también la diferenciación cultural substituta como se ha demostrado con la hermandad entre multiculturalismo identitario y neoliberalismo. En el interregno el sofismo no solo crece y se alimenta, sino que dada la caída de toda legitimidad, la mentira solo puede asomarse como performance desnudo de la no verdad, puesto que ha agotado su efecto de persuasión posible, su validez efectiva, y cualquier ápice de razón. La tecnificación del pensamiento a través del marco equivalencial de la teoría supone la codificación del sofismo como valorización sin necesidad de apelar a la razón.

Por ejemplo, el éxito universitario de la decolonialidad, ¿no es la victoria de la irracionalidad como valor? A la decolonialidad no le hace falta ni le importa la razón – que para los llamados pensadores decoloniales es ya de antemano contaminación ‘eurocéntrica’ o ‘ego-política colonial’ – sino la afirmación nómica de un absolutismo cultural y propietario. La irracionalidad prometeica de las finanzas en el momento de la subvención real converge con un neomedievalismo crítico, y de este modo las piedades y doxologías retornan como figuras luminosas de un saber que parece haber saldado sus cuentas con la Historia. La anomia de la universidad contemporánea es principalmente una crisis de legitimidad, entendida como fin de su efecto de auto-convencimiento y ejercicio del pensar singular. Y así, no es sorprendente que la irracionalidad brille, triunfe, y cobre un peso irrefutable en las medidas tecnocráticas que regulan las Humanities.

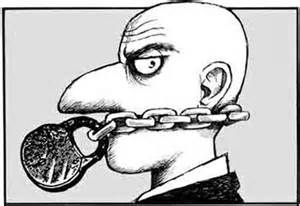

La irracionalidad comparece a la tecnificación donde todo se ventila de antemano. Pensemos, por ejemplo, en la jerigonzas concurridas como ‘¿cuál es tu marco teórico?’ o ‘¿desde donde hablas?’ ‘¿cuál es tu archivo?’. Estas indagaciones solo pueden entenderse como formas de una máquina inquisitorial que la universidad alberga como principio de autoridad ante la caída medular de su legitimidad. Sería coherente pensar, entonces, que si estamos ante una máquina confesional, solo la mentira puede ofrecer salvación o posibilidad de ‘mantenerse en pie’ sin tocar fondo, o sin que le vuelen a uno la cabeza. Justo es esto lo que esgrime en En defensa del populismo (2016) el filósofo español Carlos Fernández Liria, quien sugiere que ante la consumación de la mentira en el campo político contemporáneo, no hay verdad que esté condiciones de legibilidad, ni de escucha, ni de generar efecto alguno ante un macizo ideológico impenetrable. La única posibilidad es expresar una contramentira. ¿Pero es ésta la única forma de contestación? Podemos ‘testear’ esta pregunta en un momento decisivo del libro, y que aparece condensado en la forma de un chiste. Valdría la pena reproducir el pasaje:

“La sospecha de no ser lo suficientemente correctos en política, con todo el misterio terrorífico que esa determinación tiene en la academia norteamericana, pesó siempre sobre nuestras cabezas como una grave espada de Damocles, y todavía pesa, y no importa lo que digamos o hagamos, porque estas cosas, como todo el mundo sabe, se solucionan a nivel de sospecha y rumor y susurro malicioso. O incluso: es una cuestión de olor u honor, como el cristiano nuevo perfectamente devoto que no puede evitar caer en manos de la Cruz Verde porque todo el mundo sabe que su piel no reluce con la grasa prestada de la sobrasada. O, en palabras de algún fiscal federal asistente en la nueva serie de televisión Billions, «Si alguien dice que Charlie se folló a una cabra, aunque la cabra diga que no, Charlie se va a la tumba como Charlie el Follacabras» (225-26).

Lo que he llamado la forma sofística de la retórica contemporánea transforma a todos en Follacabras, en miembros potenciales de algún siniestro grupúsculo de Follacabras, y no importa la verdad que salga de la boca de la cabra (si es que la cabra habla), o del propio Charlie, puesto que una vez que la marca de Caín reluce sobre el pellejo de la frente, ya estamos automáticamente condenados a participar de una exposición que nos arroja al juego de cazadores y cazados. Este ha sido siempre el campo de batalla de la hegemonía, y que hoy se vuelve sistemático desde su inscripción en la equivalencialidad general. Esto es, no hay quien se escape a su lógica. Es más, no hay quien no sea, a la vez, una excepción sacrificable a esta lógica.

Pero habría otra opción: los Follacabras o los condenados pudieran también rechazar el sofismo y sus afligidas metáforas, aceptando la verdad como ascesis, esto es, como ejercicio en éxodo de todo juego hegemónico efectivo. Es lo que parece estar pidiendo Moreiras en Marranismo e Inscripción, y eso es ya bastante, y nos obliga a repensar la cacería como único juego posible. Y es el ascesis donde pensamiento y vida entran en una zona de indeterminación, y desde donde la verdad puede comparecer como alternativa al yoga acrobático que ofrece la universidad contemporánea, ya sea en su forma inquisitiva que obliga a la mentira, o en su produccionismo metabólico desplegado en el consenso, o en la politización, o en las buenas intenciones. Fue Iván Illich quien notó que el ascenso de la crítica académica monástica, y cuya secularización es la sospecha hermenéutica, coincidió con la declinación del ejercicio ascético del singular [2]. Y esto tiene sentido, puesto que la función crítica solo puede apelar a una radicalidad en expansión, siempre y cuando se retraiga de pensar la facticidad que supone la irreversibilidad del capitalismo. No es casual que Moreiras hacia el final del libro, y en réplica a una pregunta de Ángel O. Álvarez Solís, recurra al arcano del ascesis, como abandono del juego hegemónico de las mentira, y que dibujo los contornos de una vida sin principio:

“La palabra «ejercicio» puede servir si la entendemos etimológicamente, desde ex + arcare, desenterrar lo oculto, des-secretar. Digamos entonces, todo lo provisionalmente que quieras, que la infrapolítica es una forma de ejercicio en ese sentido –busca éxodo con respecto de la relación ético-política técnica, busca su destrucción desecretante, para liberar una práctica existencial otra. Yo no tendría inconveniente en usar para esto una expresión que he usado en algún otro lugar, la de «moralismo salvaje». La infrapolítica, en su condición reflexiva, es un ejercicio de moralismo salvaje, anti-político y anti-ético, porque quiere éxodo con respecto de la prisión subjetiva que constituye una relación ético-política impuesta ideológicamente sobre nosotros como consecuencia del humanismo metafísico. Sí, ese paso atrás salvaje con respecto de la relación ético-política es an-árquico, porque no se somete a principio.” (Moreiras 208).

La ascesis dice la verdad en la medida en que siempre atraviesa una hermenéutica existencial, y da un ‘paso atrás’ que renuncia a las determinaciones fundamentales de la subjetividad. El ejercicio tiene como objetivo el cuidado ante previsibilidad del síntoma. Si la ascesis es contrauniversitaria, lo es no en función anti-universitaria, sino por su instancia necesariamente atópica, ejercida como expatriación y desvinculación de todo sentido de propiedad y pertenencia comunitaria. Para el marrano no hay pasos aun por dar, sino solo un paso atrás, que es siempre el paso imposible al interior del tiempo de la morada. Esto supone abandonar el fantasma hegemónico del campo académico como avatar del pensamiento. Se piensa siempre en otro-lado. Es este también el sentido, de otra manera incomprensible, desde el cual podemos entender el intercambio epistolar entre Celan y Bachmann: “No recuerdo haber salido nunca de Egipto, sin embargo celebraré esta fiesta en Inglaterra” [3].

Ese paso atrás es el de la posibilidad imposible para seguir adelante desde un pensamiento que renuncia a la presbeia para ser radicalmente amonoteísta. ¿Podemos acaso imaginar una universidad en Egipto? Solo esta sería una universidad post-deconstructiva. Marranismo e Inscripción invita a este éxodo como única posibilidad de mantenernos en pie, y de echar adelante. Y hoy, ya no perdemos nada con intentarlo.

*Position Paper read at book workshop “Los Malos Pasos” (on Alberto Moreiras’ Marranismo e Inscripción), held at the University of Pennsylvania, January 6, 2017.

Notas

- Arturo Leyte. El paso imposible. Mexico D.F: Plaza y Valdés, 2013. p.24-53.

- Iván Illich. “Ascesis”. (Manuscript, dated 1989).

- Paul Celan & Ingeborg Bachmann. Tiempo del corazón: Correspondencia. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Economica, 2012.

I only have twelve minutes, as you know, and I would like to use them to present an idea of community to you that in my opinion dissolves the general problem community has always presented to political thought, and which I will sum up by claiming that community is, can be, the most antipolitical of all political concepts. In recent times it has been pretended that community could configure an anti-liberal or non-liberal basic concept for a new politics, the possibility of a democratic overcoming of liberal individualism. But things are not so easy, and we are now running the risk of a disavowed, but thorougly liberal, counterconcept of individualism camouflaged as a thinking of community. The problem is that such a concept of community cannot fail to be authoritarian through its very suppression of politics—we were discussing this yesterday in a session on the current crisis of the Podemos political party in Spain.

I only have twelve minutes, as you know, and I would like to use them to present an idea of community to you that in my opinion dissolves the general problem community has always presented to political thought, and which I will sum up by claiming that community is, can be, the most antipolitical of all political concepts. In recent times it has been pretended that community could configure an anti-liberal or non-liberal basic concept for a new politics, the possibility of a democratic overcoming of liberal individualism. But things are not so easy, and we are now running the risk of a disavowed, but thorougly liberal, counterconcept of individualism camouflaged as a thinking of community. The problem is that such a concept of community cannot fail to be authoritarian through its very suppression of politics—we were discussing this yesterday in a session on the current crisis of the Podemos political party in Spain.

En defensa el populismo (Catarata, 2016), del pensador Carlos Fernández Liria, es un libro espinoso que busca instalarse con vehemencia al interior del debate en torno a la política española de los últimos años. Por supuesto, es también un libro abiertamente comprometido con el ascenso de Podemos, y su líder Pablo Iglesias, y sobra decir que su defensa de la ‘centralidad del tablero’ no se presta a equívocos. En efecto, en el prólogo del libro, Luis Alegre Zahonero celebra que Fernández Liria brinde su apoyo a la disputa por los nombres del enemigo, y que recupere para la izquierda nociones como democracia, ciudadano, derechos, o institución en línea con la obra elemental populista: la construcción de un pueblo. El punto de partida de Fernández Liria es volver sobre la textura del lenguaje, y desde ahí colonizar su gramática hasta efectuar un ‘nuevo sentido común’. Aunque Fernández Liria sitúa el problema en un arco de larga duración: al menos desde Platón y Sócrates, el lenguaje siempre ha obedecido al habla en el lenguaje del otro, léase del poderoso, y solo así ha sido capaz de generar escucha.

En defensa el populismo (Catarata, 2016), del pensador Carlos Fernández Liria, es un libro espinoso que busca instalarse con vehemencia al interior del debate en torno a la política española de los últimos años. Por supuesto, es también un libro abiertamente comprometido con el ascenso de Podemos, y su líder Pablo Iglesias, y sobra decir que su defensa de la ‘centralidad del tablero’ no se presta a equívocos. En efecto, en el prólogo del libro, Luis Alegre Zahonero celebra que Fernández Liria brinde su apoyo a la disputa por los nombres del enemigo, y que recupere para la izquierda nociones como democracia, ciudadano, derechos, o institución en línea con la obra elemental populista: la construcción de un pueblo. El punto de partida de Fernández Liria es volver sobre la textura del lenguaje, y desde ahí colonizar su gramática hasta efectuar un ‘nuevo sentido común’. Aunque Fernández Liria sitúa el problema en un arco de larga duración: al menos desde Platón y Sócrates, el lenguaje siempre ha obedecido al habla en el lenguaje del otro, léase del poderoso, y solo así ha sido capaz de generar escucha. Recent egregious instances of unprofessional behavior that must remain unexplicit for the sake of third parties motivate this open letter. The signatories wish to reject exclusionary practices—happening with increasing frequency–against scholars interested in the theoretical field of infrapolitics, many of them affiliated to departments of Spanish and Latin American Studies in US universities. Ranging from denying researchers the right to share their work with interested colleagues (blocking invitations, blocking participation in professional conferences), through passive and active censorship of research agendas, to active discrimination in the job market, these practices are most often exerted upon graduate students and junior faculty–the most vulnerable members in our profession. Those of us who are old enough to remember previous moments in the life of the field, for instance, early days of deconstruction, or subaltern studies, or feminism, or queer studies, are also experienced enough to know that the damage that this kind of attitude does to intellectual practice in general is insidious. Freedom of expression is threatened at its core by the setting of limits of discourse one must not transgress. The consequence of such behavior is far from only affecting specifically marked scholars every now and then. More importantly, it has internal institutional effects as it produces and performs ideological subordination that should be abhorrent to common university folk in the name of plain decency and the dignity of thought. And, not least, it hurts careers, or keeps them from taking off without compliance. To be sure, no one is obliged to invite anyone at all to engage in a conversation, but there is a line that should not be crossed, and that is the line of the explicit ban of trends of thought from certain institutional spaces because they are deemed dangerous to a professional discourse that must apparently be policed by privileged self-appointed guardians. We are calling for basic respect for diversity and freedom of thought, and we are denouncing the sinister effects of intellectual repression. In the middle of a political transition whose bearing upon university life is to be feared, at a time in which lists of inconvenient professors are being prepared by the radical right, those of us signing this letter wish to express our rejection of craven institutional censorship based on what to us is only hatred of experimentation and innovation in thought. We welcome disagreement and critical engagement, not the imposition of ideological compliance. By their very nature, these events tend to happen in relative secrecy and impunity, and publicly explicit resistance to the undermining of freedom of expression in our general field of Spanish and Latin American Studies is perhaps rare. We fear this letter will not be enough, but we are prepared to continue in our efforts.

Recent egregious instances of unprofessional behavior that must remain unexplicit for the sake of third parties motivate this open letter. The signatories wish to reject exclusionary practices—happening with increasing frequency–against scholars interested in the theoretical field of infrapolitics, many of them affiliated to departments of Spanish and Latin American Studies in US universities. Ranging from denying researchers the right to share their work with interested colleagues (blocking invitations, blocking participation in professional conferences), through passive and active censorship of research agendas, to active discrimination in the job market, these practices are most often exerted upon graduate students and junior faculty–the most vulnerable members in our profession. Those of us who are old enough to remember previous moments in the life of the field, for instance, early days of deconstruction, or subaltern studies, or feminism, or queer studies, are also experienced enough to know that the damage that this kind of attitude does to intellectual practice in general is insidious. Freedom of expression is threatened at its core by the setting of limits of discourse one must not transgress. The consequence of such behavior is far from only affecting specifically marked scholars every now and then. More importantly, it has internal institutional effects as it produces and performs ideological subordination that should be abhorrent to common university folk in the name of plain decency and the dignity of thought. And, not least, it hurts careers, or keeps them from taking off without compliance. To be sure, no one is obliged to invite anyone at all to engage in a conversation, but there is a line that should not be crossed, and that is the line of the explicit ban of trends of thought from certain institutional spaces because they are deemed dangerous to a professional discourse that must apparently be policed by privileged self-appointed guardians. We are calling for basic respect for diversity and freedom of thought, and we are denouncing the sinister effects of intellectual repression. In the middle of a political transition whose bearing upon university life is to be feared, at a time in which lists of inconvenient professors are being prepared by the radical right, those of us signing this letter wish to express our rejection of craven institutional censorship based on what to us is only hatred of experimentation and innovation in thought. We welcome disagreement and critical engagement, not the imposition of ideological compliance. By their very nature, these events tend to happen in relative secrecy and impunity, and publicly explicit resistance to the undermining of freedom of expression in our general field of Spanish and Latin American Studies is perhaps rare. We fear this letter will not be enough, but we are prepared to continue in our efforts. Carlos Casanova’s short book Estética y Producción en Karl Marx (ediciones metales pesados, 2016), a condensed version of his important and much longer doctoral thesis, advances a thorough examination of Marx’s thought, and unambiguously offers new ways for thinking the author of Das Kapital and beyond. Although the title could raise false expectations of yet another volume on ‘Marxism and Aesthetics’, or, more specifically, a hermeneutical reconstruction of a lost ‘aesthetics’ in Marx, these are neither the concerns nor aims of Casanova’s book. Instead, he does not hesitate to claim that there are no aesthetics in Marx’s thought derivative from German theories of romantic idealism, conceptions of the beautiful, or the faculty of judgment in the Kantian theory of the subject and critique.

Carlos Casanova’s short book Estética y Producción en Karl Marx (ediciones metales pesados, 2016), a condensed version of his important and much longer doctoral thesis, advances a thorough examination of Marx’s thought, and unambiguously offers new ways for thinking the author of Das Kapital and beyond. Although the title could raise false expectations of yet another volume on ‘Marxism and Aesthetics’, or, more specifically, a hermeneutical reconstruction of a lost ‘aesthetics’ in Marx, these are neither the concerns nor aims of Casanova’s book. Instead, he does not hesitate to claim that there are no aesthetics in Marx’s thought derivative from German theories of romantic idealism, conceptions of the beautiful, or the faculty of judgment in the Kantian theory of the subject and critique.