En el artículo “Una patada en la mesa”, publicado el pasado 17 de Mayo, el pensador David Soto Carrasco pone sobre la mesa dos estrategias fundamentales para acercarnos sobre lo que viene acechando a la política española (aunque para los que estamos interesados en pensar la política más allá de un caso nacional, España es solamente un paradigma de la tarea central para el pensamiento político). Primero, Soto señala, contra los críticos convencionales tanto de la derecha como de la izquierda, que el nuevo acuerdo entre Podemos-Izquierda Unida no es una radicalización ultraizquierdista de la nueva fuerza política de Pablo Iglesias. Y segundo, sugiere que el nuevo acuerdo tampoco es un “acto de resistencia” en el sentido de una mera filiación para mantenerse a flote en la escena de la política nacional.

Soto Carrasco nos dice que se trata de un acto político de madurez que convoca a la ciudadanía española a través de una táctica de transversalidad. La alianza con Izquierda Unida, de esta manera, no estaría implicada en arribismo hegemónico, sino en nuevas posibilidades para “dibujar líneas de campo” y enunciar otras posiciones por fuera del belicismo gramsciano (guerra de posiciones). Soto Carrasco le llama a esto “sentido común”, pero le pudiéramos llamar democracia radical, o bien lo que en otra parte he llamado, siguiendo a José Luis Villacañas, deriva republicana. Conviene citar ese momento importante del artículo de Soto Carrasco:

“En política, la iniciativa depende fundamentalmente de la capacidad de enunciar tu posición, la posición del adversario pero también de definir el terreno de juego. Si se quiere ganar el partido, no solo basta con jugar bien, sino que hay que dibujar las líneas del campo. Dicho con otras palabras si se quiere ganar el cambio hay que recuperar la capacidad de nombrar las cosas y redefinir las prioridades. Generalmente esto lo hacemos a través de lo que llamamos sentido común. Para ello, la izquierda (como significante) ya no es determinante” [1].

El hecho que los partidos políticos y sus particiones ideológicas tradicionales estén de capa caída hacia el abismo que habitamos, es algo que no se le escapa ni al más desorientado viviente. Contra el abismo, el sentido común supone colocar al centro del quehacer de la política las exigencias de una nueva mayoría. Pero esa gran mayoría, en la medida en que es una exigencia, no puede constituirse como identidad, ni como pueblo, ni como representación constituida. La gran política no puede radicarse exclusivamente como restitución de la ficción popular bajo el principio de hegemonía.

En los últimos días he vuelto sobre uno de los ensayos de Il fuoco e il racconto (Nottetempo 2014) de Giorgio Agamben, donde el pensador italiano argumenta que justamente de lo que carecemos hoy es de “hablar en nombre de algo” en cuanto habla sin identidad y sin lugar [2]. La política (o el populismo) habla hoy en nombre de la hegemonía; como el neoliberalismo lo hace en nombre de la técnica y de las ganancias del mercado, o la universidad en nombre de la productividad y los saberes de “campos”. Hablar desde el mercado, la universidad, o el gobierno no son sino un mismo dispositivo de dominación, pero eso aun no es hablar en nombre de algo. Agamben piensa, en cambio, en un habla abierta a la impotencia del otro, de un resto que no se subjetiviza, de un pueblo que no se expone, y de una lengua que no llegaremos a entender. El mayor error de la teoría de la hegemonía es abastecer el enunciado del ‘nombre’ con fueros que buscan armonizar (en el mejor de los casos) y administrar el tiempo de la vida en política.

Por eso tiene razón José Luis Villacañas cuando dice que el populismo es política para idiotas (Agamben dice lo mismo, sin variar mucho la fórmula, que hoy solo los imbéciles pueden hablar con propiedad). Podríamos entender – y esta sería una de las preguntas que se derivan del artículo de Soto Carrasco – el dar nombre, ¿desde ya como función política que abandona la hegemonía, y que contiene en su interior el rastro poshegemónico? ¿No es ese “sentido común” siempre ya “sentido común” de la democracia en tanto toma distancia de la hegemonía como producción de ademia? Si la democracia es hoy ilegítima es porque sigue dirigiendo las fuerzas de acción propositiva hacia la clausura del significante “Pueblo” en nombre de un “poder constituido”.

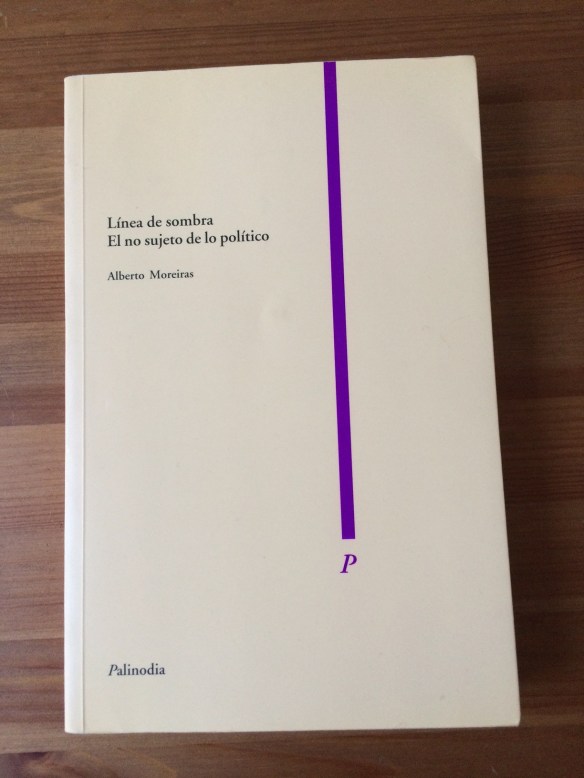

En este sentido estoy de acuerdo con Moreiras cuando dice que la poshegemonía “nombra” la posibilidad de cualquier posible invención política en nuestro tiempo [3]. Es una brecha del pensamiento. Lo que siempre “nombramos” nunca habita en la palabra, en el concepto, o en prefijo, sino en la posibilidad entre nosotros y la potencia de imaginación para construir algo nuevo. Y eso es lo que pareciera constituir el olvido de los que permanecen enchufados a la política de la hegemonía, o la hegemonía como siempre reducible de una manera u otra a la política.

Soto Carrasco propone una transversalidad entendida como “principio político y nueva cultura política”. Y esto, nos dice, es lo decisivo para un nuevo rumbo y renovación de la política. La transversalidad es momento y estrategia de invención de las propias condiciones de la política real, y por eso necesariamente se escapa al orden de la hegemonía o del doblez en “Pueblo”. ¿Qué tipo de transversalidad? ¿Y cómo hacerlo sin volver a dibujar un mapa de alianzas políticas y sus digramacionoes de poder, siempre en detrimento del orden institucional y de la división de poderes? Fue esto lo que en buena medida limitó y finalmente llevó a la ruina y agotamiento la capacidad de ascenso del progresismo en América Latina durante este último ciclo histórico de luchas más reciente [4]. La transversalidad no puede ser alianza meramente con fines electoralistas o populistas de un lado u otro péndulo del poder.

A la transversalidad habría que superponerla con su suplemento: una segmentariedad inconmensurable, poshegemónica, y anti-carismática. Como lo ha notado recientemente José Luis Villacañas, quizás varíen las formas en que aparezca el lenguaje: “Es posible que lo que yo llamo republicanismo no sea sino la mirada de un senior de aquello que para alguien jóvenes es populismo…” [5]. Pero si las palabras y los términos fluctúan (siempre son otros para los otros), lo único que queda es la pregunta: ¿en nombre de qué?

Más allá de la palabra o el concepto, la política que viene tendría que estar en condición de hablar-se en nombre del fin de la hegemonía y la identidad. Solo así sus nombres del presente podrían ser democracia poshegemónica, populismo, comunismo del hombre solo, transversalidad, institucionalismo republicano, o división de poderes…

Notas

- David Soto Carrasco. “Una patada al tablero”. http://www.eldiario.es/murcia/murcia_y_aparte/patada-tablero_6_516958335.html

- Giorgio Agamben. Il fuoco e il racconto. Nottetempo, 2014.

- Alberto Moreiras. “Comentario a ‘una patada al tablero’, de David Soto Carrasco. https://infrapolitica.wordpress.com/2016/05/18/comentario-a-una-patada-al-tablero-de-david-soto-carrasco-por-alberto-moreiras/

- Ver, “Dossier: The End of the Progressive Cycle in Latin America” (ed. Gerardo Muñoz, Alternautas Journal, n.13, 2016). Ver en particular la contribución de Salvador Schavelzon sobre las alianzas en Brazil, “The end of the progressive narrative in Latin America”. http://www.alternautas.net/blog?tag=Dossier

- José Luis Villacañas. “En La Morada”: “Es posible que lo que yo llamo republicanismo no sea sino la mirada propia de un senior de aquello que para alguien más joven es populismo. La res publica también provoca afectos, como el pueblo, aunque puede que los míos sean ya más tibios por viejos. Su gusto por las masas es contrario a mi gusto por la soledad. Yo hablo en términos de legitimidad y ellos de hegemonía; yo de construcción social de la singularidad de sujeto, y ellos de construcción comunitaria; yo de reforma constitucional, y ellos de conquistas irreversibles; yo de carisma antiautoritario, y ellos de intelectual orgánico. En suma, yo hablo de Weber y ellos de Gramsci, dos gigantes europeos. Es posible que una misma praxis política permita más de una descripción. Es posible que todavía tengamos que seguir debatiendo cuestiones como la de la fortaleza del poder ejecutivo, algo central hacia el final del debate. En realidad yo no soy partidario de debilitarlo, sino que sólo veo un ejecutivo fuerte en el seno de una división de poderes fuerte.” http://www.levante-emv.com/opinion/2016/05/17/morada/1418686.html

In the last chapter of Heterogeneity of Being: On Octavio Paz’s Poetics of Similitude (UPA, 2015), Marco Dorfsman tells of how he once encountered a urinal in the middle of a library hallway. It was a urinal possibly waiting to be replaced or already re-moved from a public bathroom. The details did not matter as it recalled the origin of the work of art, and of course Duchamp’s famous readymade, originally lost only to be replicated for galleries and mass spectatorship consumption. Duchamp’s urinal, or for that matter any manufactured ‘displaced thing’ reveals the essence of technology, at the same time that it profanes its use well beyond appropriation and instrumentalization. I recall this late anecdote in the book, since Dorfsman’s strategy in taking up Octavio Paz’s poetics is analogous to the dis-placing of a urinal. In Heterogeneity of Being, Paz is de-grounded from the regional and linguistic archive, dis-located from the heritage and duty of national politics, and transported to a preliminary field where the aporetic relation between thought and poem co-belong without restituting the order of the Latianermicanist reason.

In the last chapter of Heterogeneity of Being: On Octavio Paz’s Poetics of Similitude (UPA, 2015), Marco Dorfsman tells of how he once encountered a urinal in the middle of a library hallway. It was a urinal possibly waiting to be replaced or already re-moved from a public bathroom. The details did not matter as it recalled the origin of the work of art, and of course Duchamp’s famous readymade, originally lost only to be replicated for galleries and mass spectatorship consumption. Duchamp’s urinal, or for that matter any manufactured ‘displaced thing’ reveals the essence of technology, at the same time that it profanes its use well beyond appropriation and instrumentalization. I recall this late anecdote in the book, since Dorfsman’s strategy in taking up Octavio Paz’s poetics is analogous to the dis-placing of a urinal. In Heterogeneity of Being, Paz is de-grounded from the regional and linguistic archive, dis-located from the heritage and duty of national politics, and transported to a preliminary field where the aporetic relation between thought and poem co-belong without restituting the order of the Latianermicanist reason.

Federico Galende’s new book Comunismo del hombre solo (Catálogo, 2016) cannot be read as just an essay, but rather as a gesture that point to a common hue of humanity. This hue is the intensity of blue – instead of the zealous red, the morning yellow, or the weary white – the intensity that withdraws to an ethereal plane of the common. In a recent book on Picasso, T.J. Clark reminds us that the palate blue of the Spanish artist’s early period paved the way for the entry into the temporality of the modern, while demolishing the bourgeois interior and its delicate intimacy of lives that thereafter became possessed by work and display [1].

Federico Galende’s new book Comunismo del hombre solo (Catálogo, 2016) cannot be read as just an essay, but rather as a gesture that point to a common hue of humanity. This hue is the intensity of blue – instead of the zealous red, the morning yellow, or the weary white – the intensity that withdraws to an ethereal plane of the common. In a recent book on Picasso, T.J. Clark reminds us that the palate blue of the Spanish artist’s early period paved the way for the entry into the temporality of the modern, while demolishing the bourgeois interior and its delicate intimacy of lives that thereafter became possessed by work and display [1].

La vita sensibile (2011) is Emanuele Coccia’s first book to be translated into English. Rendered as Sensible Life: a micro-ontology of the image (Fordham U Press, 2016), it comes with an insightful prologue by Kevin Attell, and it belongs to the excellent “Commonalities” series edited by Timothy Campbell. We hope that this is not the last of the translations of what already is Coccia’s prominent production that includes, although it is not limited to La trasparenza delle immagini: Averroè e l’averroismo (Mondadori, 2005), Angeli: ebraismo, cristianesitimo, Islam (co-ed with G. Agamben, 2011), and most recently Il bene nelle cose: la pubblicità come discorso morale (2014). One should take note that in Latin America – particularly in Chile and Argentina – Coccia’s books have been translated for quite a while, and have been part of a lively debate on contemporary thought. We hope that a similar fate is destined in the United States. For some of some of us working within the confines of the Latinamericanist reflection, an encounter with Coccia has grown out of our continuous exchange with friends like Rodrigo Karmy, Gonzalo Diaz Letelier, and Manuel Moyano. It would be superfluous to say that Coccia’s work is nested in the so called contemporary ‘Italian Philosophy’ (pensiero vivente, in Roberto Esposito’s jargon), although one would be committing a certain violence to reduce it to another ‘theory wave’ so rapidly instrumentalized in the so called ‘critical management’ within the North American university.

La vita sensibile (2011) is Emanuele Coccia’s first book to be translated into English. Rendered as Sensible Life: a micro-ontology of the image (Fordham U Press, 2016), it comes with an insightful prologue by Kevin Attell, and it belongs to the excellent “Commonalities” series edited by Timothy Campbell. We hope that this is not the last of the translations of what already is Coccia’s prominent production that includes, although it is not limited to La trasparenza delle immagini: Averroè e l’averroismo (Mondadori, 2005), Angeli: ebraismo, cristianesitimo, Islam (co-ed with G. Agamben, 2011), and most recently Il bene nelle cose: la pubblicità come discorso morale (2014). One should take note that in Latin America – particularly in Chile and Argentina – Coccia’s books have been translated for quite a while, and have been part of a lively debate on contemporary thought. We hope that a similar fate is destined in the United States. For some of some of us working within the confines of the Latinamericanist reflection, an encounter with Coccia has grown out of our continuous exchange with friends like Rodrigo Karmy, Gonzalo Diaz Letelier, and Manuel Moyano. It would be superfluous to say that Coccia’s work is nested in the so called contemporary ‘Italian Philosophy’ (pensiero vivente, in Roberto Esposito’s jargon), although one would be committing a certain violence to reduce it to another ‘theory wave’ so rapidly instrumentalized in the so called ‘critical management’ within the North American university.